A tweet by the always awesome Mike Rugnetta in the wake of early Jurassic World reviews got me thinking; how realistic does media need to be?

Some critics and fans have been questioning the accuracy of the movie, but this leaves several important questions. What does it mean when the audience asks for a movie to be more ‘realistic’? How realistic can a movie about a Dinosaur Theme Park in the 21st Century be? Which reality are we even talking about?

(Full disclosure: I have not yet seen Jurassic world, but I am a RIDICULOUS fan of the trilogy, especially Lost World, which is criminally under-rated…)

It’s important to note at this point that there are several ‘realities’ at play here. The first and most obvious level of realism that the film can be taken to task over (though perhaps not the most important reality for the fans, but we’ll get to that in a bit), is how scientifically accurate the film is. This line of criticism revolves around the audience questioning how realistic the film is in terms of the scientific knowledge presented on screen. The most hard-line cynic might question the entire premise of the movie; is it even scientifically feasible to re-create the dinos from mosquitos caught in amber? Is the whole concept utterly unbelievable, and therefore, is the whole film built upon a ridiculous notion in the first place?

However, others might suspend the disbelief with the general premise, accepting it despite its potential flaws, and instead claim the film lacks realism in its portrayal of the dinos. Shouldn’t dinosaurs have feathers? Why didn’t the film include any new discoveries made in the world of dinosaurs since the first film came out in 1993? How accurate is the a-sexual breeding?

Still others might question the realism of some of the action sequences, to use an example from another movie, the scene from the Hobbit, Battle of the Five Armies, was much ridiculed for its portrayal (or non-portrayal in this case) of gravity, without many people pointing out that what they were questioning the realism of was an elf running away from orcs, so reality is a hard thing to claim here in the first place!

But there is also the reality of the Jurassic Park franchise itself. Over the years, Jurassic Park has developed its own mythos (You didn’t say the magic word…), its sets of practices, its rules, and its own in-world reality. Some critics and fans have pointed out the Jurassic World doesn’t stay true to the ethos and timbre of some of the earlier movies; that Jurassic World isn’t a real Jurassic Park movie, and that it’s not ‘Jurassic Park-y’ enough. (interestingly, this isn’t the first time Spielberg has had that claim leveled against him… Crystal Skull anyone?!)

There’s also a large number of other realities that I haven’t considered or detailed here, including the general public’s understanding of Dinosaurs, and the non-diehard fans’ understanding of Jurassic park, and many other Discourses and levels of reality at play.

So what are we to make of this? Are these all equally valid claims on a realistic portrayal of dinosaurs. Is one more worthy than the other? Can we ever practically expect a movie to be 100% realistic?

One potential place to turn to when considering this is an understanding of translation. When we translate from one medium into another (i.e. from reality into a movie), what can we reasonably expect to be included for the new portrayal in the new medium to be considered accurate? The act of translation into a new medium ultimately involves the purposeful selection of aspects and features to include, and of aspects and features to ignore. This process reveals much about how the original medium is thought about, showing what the designer/artists/writers views as important, which aspects of the physical reality are highlighted and emphasized, and which aspects are left out or minimized. It also works to suggest how we the audience should think about the new medium. In other words, translation into a new medium show us how to ‘think’ about reality, and how reality is thought about for us by writers, designers, artists etc. Translation of reality into a new medium serves as a stylized selective representation of social realities that reflect and reveal the ideologies of the designers of these new mediums. This is perhaps best summed up in the Italian adage ‘traduttore, traditore‘ which (extremely ironically) roughly translates as ‘to translate is to betray’. When we translate from one medium to another, certain decisions must be made about what to include and what to exclude. A map for example, can’t realistically be expected to show the exact position of ever tree, car, and person in order to realistically serve as a usable translation of reality (well, except for the Marauder’s Map, thanks J.K Rowling!)

So, given that realism can never truly be 100% achieved, should we even bother to try to present anything realistically at all? Should we just drop the facade and acknowledge that what we are watching on never can, and never will be, 100% reality, given that at some point certain aspects of reality can’t be shown and experienced in this medium? Well, Bertolt Brecht suggested just that in the 1920s with regards to theatre. He suggested that when watching a play, the audience should be reminded that what they are watching is not real, that it is just a work of fiction, and that they are an audience watching a staged event. He suggested that the audience should remain objective (which is arguably unachievable, but that is a whole other discussion) and emotionally divested from the play in order to be able to analyze and critically unpack the spectacle before them. However, this idea has never sat well with me, and I’m not sure I agree. Emotional engagement is one of the most wonderful things about media. I wouldn’t have binge-watched as many series as I have if I wasn’t emotionally invested in the story/characters. Many media forms rely heavily upon emotional investment, and to deny it seems harsh and reductive.

So how can we be question the realism of a media portrayal whilst still being invested in the story and the characters presented to us? Well, Scott McCloud suggests that there can be a happy balance between an audience’s understanding of the claims to reality of a piece of media, whilst still allowing for an understanding that what is being presented to the audience is a stylized and purposeful representation and translation of reality. He does so by discussing Comic Book art, and using examples taken from the works of Will Eisner.

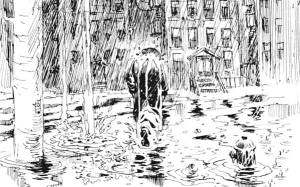

McCloud suggests that the audience may understand, at some level, that what they are viewing in Eisner’s work is a representation or translation of New York. They may, depending on their experiences and knowledge, relate the image to their experiences of New York, allowing them to draw upon their sights, sounds, smells, taste, and feels of New York to fully flesh-out and realize this image. McCloud suggests in order to fully appreciate media, we have to become invested. In fact, he goes as far to suggest we can’t help BUT become invested in media. He calls the process ‘closure’ and suggests that it’s subconscious, and something we do automatically. When approaching a piece of media we attempt to contextualize it; we attempt to fill in the gaps and the information not presented to us, and to imagine not only what is shown to us, but everything outside of the borders of the images as well. McCloud suggests that we unleash our imagination to fill in the gaps presented to us; we draw upon our understanding and experiences of other media texts (intertextuality, see Bakhtin for more on this) and upon our understanding of our own life experiences (extratextuality – my New York may be different from your reality of New York), meaning that each person experiences media differently and brings differing and varied experiences with them when approaching a media form.

On top of this, McCloud suggests on another level we can see that what we are viewing is the artist’s portrayal of that New York. What we see is clearly Eisner’s New York; he is purposefully and stylistically representing New York to and for us. As such, reality here becomes something that is co-constructed through the author, the audience writ-large, and the individual’s personal understanding of other texts (intertextuality) and their lived experiences of the world (extratextuality). The representation of New York is not real in the traditional sense (and arguably, because of translation = betrayal, never truly can be), but it is not entirely baseless and removed from reality.

Again, as seems to be a reoccurring theme on my blogs/work in general, the dichotomy between real and unreal is not that clear cut. There are several reals, and a sliding scale that is personal to each user and their understanding of reality and of differing media texts.

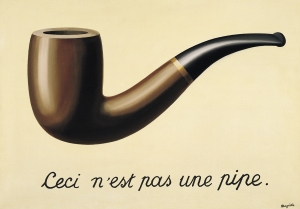

I’ll leave you with a work of art by Margritte that manages to say in 5 words what I’ve just said in 1500…

So what do you think? How can we understand reality in media? Is reality a realistic goal to aim for? Should we be honest about the ability of media to portray reality, or is it worth maintaining the facade?